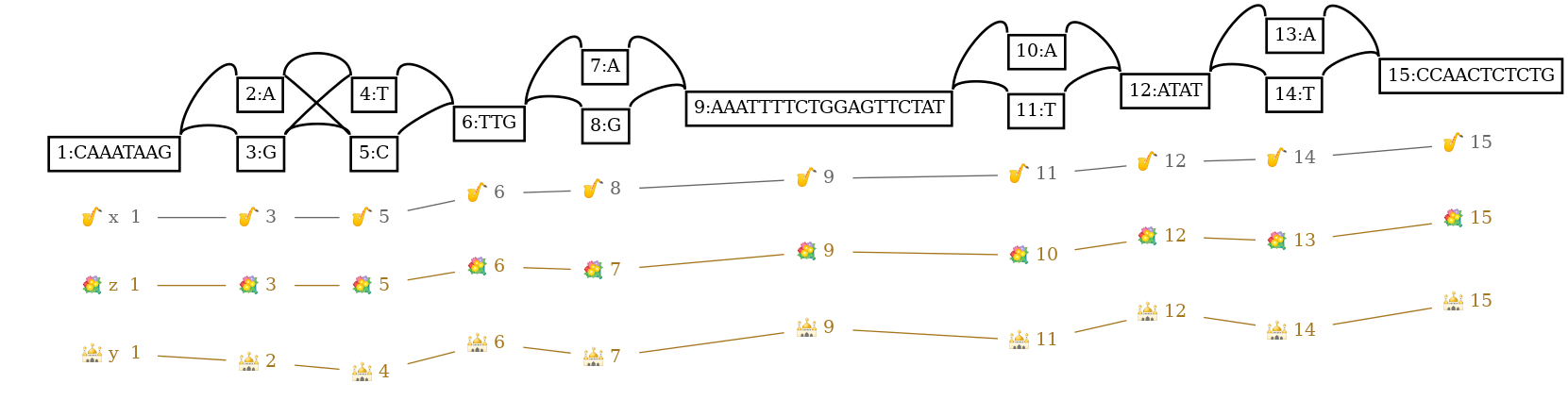

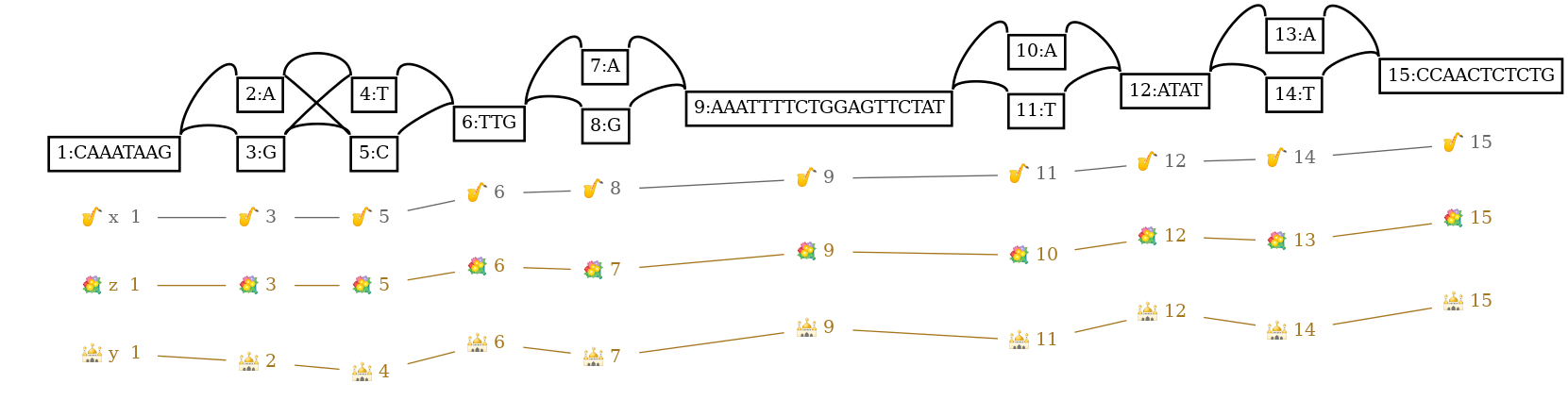

Variation graphs combine sequences (usually DNA) with information about variation between them. They can be used to represent the mutual alignment of multiple genomes, or more simply, a single reference and variation found in a population. In these graphs, nodes are labeled with sequences. Edges represent allowed linkages between nodes. Paths, or walks traversing a series of nodes, represent sequences of interest.

To interact with these graphs in precise, programmatic ways, we need to be able to identify their basic elements. This is the core motivation behind the HandleGraph abstraction used in odgi and other dynamic graph implementations in libbdsg. Because DNA sequence graphs have two strands, we need a more precise way of addressing elements in the graph than nodes, which implicitly represent both strands. The handle, which is the core concept in the Handle Graph abstraction, allows us to refer to one strand of a single node, which is the smallest addressable unit in a variation graph. Nodes have numeric identifiers (or _ID_s), and associated sequences. Edges link two handles. Paths are a series of steps which link a path identifier and a handle. Breaking this down (with reference to the C++ types), we have a set of references to graph elements:

handle_t: an oriented traversal of a node (an opaque 64-bit identifier)id_t: a node identifier (a 64-bit number)edge_t: a pair of handle_ts, where the edge is directed from the first member of the pair to the secondpath_handle_t: a reference to a path (an opaque 64-bit identifier)step_handle_t: a reference to a single step of a path on one node traversal (an opaque 128-bit identifier)The handle types are “opaque” in that they don’t directly correspond to an external identifier. For instance, the path_handle_t is just a 64-bit type, not a path name that would have been used in the GFA serialization that we loaded the graph from. The abstraction provides no guarantees about the order or meaning of the identifiers, but they are guaranteed to be stable as long as we don’t modify the graph.

You might wonder why we use these opaque references to these elements, rather than more literal identifiers. For instance, we could refer to paths by their names, and steps by path names and indexes in the path. We could just refer to nodes by their IDs.

The basic problem is that the representation of large, dynamic sequence graphs requires careful data structure design that often makes accessing elements by their literal names expensive. Except for very small or simple graphs, we can’t expect to be able to save a copy of each path name for every node it traverses. Instead, we encode some identifier that refers to the path. By using a generic identifier, we are able to encode the reference in a succinct, packed, or even implict manner that can be memory efficient.

Graph implementations that provide the HandleGraph API can thus have internal identifiers for graph elements that provide good performance for functions that interact with, query, or traverse the graph. Defining an abstract handle type allows each implementation to choose the right internal identifier model to use. In the HandleGraph API, functions are provided to convert between these internal identifiers and external ones. For instance, given a handle_t, you can ask the graph to tell you what node id_t and orientation (forward or reverse complement) it represents. We can ask the graph to give us the path_handle_t corresponding to a given path name, or find which path_handle_t and handle_t a given step_handle_t references.

Naive implementations of graph genomic data structures can consume tens of bytes per input graph. So a GFA file of 30GB, a typical size for a whole human genome graph including the 1000 Genomes Projects variation, might be impossible to load on typical systems available (as of 2020). (The initial VG implementation required 300GB to load the 30GB human genome variation graph.) HandleGraph implementations developed by the vgteam resolve this issue through careful use of succinct data structures. For most of these implementations, including odgi, the in-memory size of the graph data structures is around the same as the uncompressed input GFA. At the same time, these models provide efficient random access to (and in most cases, modification of) all of the graph elements.

Our goal with the HandleGraph API is to provide a consistent and reasoned interface to these graphs that allows for the development of algorithms independent of the particular internals of a given graph data structure. This frees users (bioinformatics and genomics researchers and developers) to focus on algorithms that operate at a higher level, without worrying about the details of efficient graph data structure implementations. Our hope is that, by working with this consistent interface, we can develop libraries of standard algorithms that achieve common goals in graph genomic operations, thus reducing the effort required to work with genome graphs.

The libhandlegraph APIs describe a hierarchy of increasingly complex capabilities, from simple static variation graphs without paths, to mutable graphs with paths and positional indexes.

This hierarchy allows us to build a consistent interface to implementations that may be optimial in a particular application but which lack generic functionality. For example, a static graph which cannot be modified is usually more efficient in terms of memory and access time than a dynamic graph, but it will not be able to match parts of the API which require modification of the graph.

In this document, we’ll avoid the complexity of this C++ API hierarchy, and focus on the most generic type of graph, the MutablePathDeletableHandleGraph model implemented in odgi, the PackedGraph and HashGraph from libbdsg. This model allows both query and modification (deletion, addition, division, unification) of all graph elements. As such, it is suitable for generic operations on genome graphs, both their construction and interrogation.

Most of the elements in the HandleGraph API are wrapped in a python module. Python makes for good pseudocode, and so we can use it here to provide some examples of how to work with the HandleGraph abstraction.

Given a graph in GFA format, we can build the odgi serialization of it using odgi build.

H VN:Z:1.0

S 1 CAAATAAG

S 2 A

S 3 G

S 4 T

S 5 C

S 6 TTG

S 7 A

S 8 G

S 9 AAATTTTCTGGAGTTCTAT

S 10 A

S 11 T

S 12 ATAT

S 13 A

S 14 T

S 15 CCAACTCTCTG

P x 1+,3+,5+,6+,8+,9+,11+,12+,14+,15+ 8M,1M,1M,3M,1M,19M,1M,4M,1M,11M

P y 1+,2+,4+,6+,7+,9+,11+,12+,14+,15+ 8M,1M,1M,3M,1M,19M,1M,4M,1M,11M

P z 1+,3+,5+,6+,7+,9+,10+,12+,13+,15+ 8M,1M,1M,3M,1M,19M,1M,4M,1M,11M

L 1 + 2 + 0M

L 1 + 3 + 0M

L 2 + 4 + 0M

L 2 + 5 + 0M

L 3 + 4 + 0M

L 3 + 5 + 0M

L 4 + 6 + 0M

L 5 + 6 + 0M

L 6 + 7 + 0M

L 6 + 8 + 0M

L 7 + 9 + 0M

L 8 + 9 + 0M

L 9 + 10 + 0M

L 9 + 11 + 0M

L 10 + 12 + 0M

L 11 + 12 + 0M

L 12 + 13 + 0M

L 12 + 14 + 0M

L 13 + 15 + 0M

L 14 + 15 + 0MTransforming the graph into odgi’s succinct self index:

We can now load this into python, using the odgi python module:

First, we need to make sure our PYTHONPATH environment variable points to the directory where our python module file lives. Assuming we built odgi in our home directory, we could do this:

Now we can load the graph and check how big it is:

We can examine an individual node:

h = g.get_handle(9)

g.get_id(h) # returns 9

g.get_is_reverse(h) # False, by default, we get the forward handle

r = g.get_handle(9, True) # get the reverse handle

g.get_is_reverse(r) # True, this handle is reverse

print(g.get_sequence(h)) # AAATTTTCTGGAGTTCTAT --- same as the node in the graph

print(g.get_sequence(r)) # ATAGAACTCCAGAAAATTT --- the reverse complementAnd we can check which paths overlap nodes:

h = g.get_handle(11)

g.for_each_step_on_handle(h,

lambda s: print(g.get_path_name(g.get_path_handle_of_step(s))))

# x

# y

g.for_each_step_on_handle(g.get_handle(9),

lambda s: print(g.get_path_name(g.get_path_handle_of_step(s))))

# x

# y

# zMatching the C++ API, most of the methods of iterating over elements in the graph use callback functions (note our use of lambda’s above). In the current version of the python API, this causes some difficulty, as python lacks true functional closures and prevents assignments within callbacks. Future versions of this API we provide generator functions thot support memory-efficient and pythonic iteration over graph elements.

For instance, to iterate over our nodes, we can call for_each_handle, which will invoke a callback for each forward handle in our graph.

g.for_each_handle(lambda h: print(g.get_id(h), g.get_sequence(h)))

# writes out each node id and its sequenceWe can enumerate the paths and get their names:

And we can iterate over the steps in a given path, finding which node and orientation each step has:

# a function to call for each step in the path

def process_step(s):

h = g.get_handle_of_step(s) # gets the handle (both node and orientation) of the step

is_rev = g.get_is_reverse(h)

id = g.get_id(h)

return str(id) + ("+" if not is_rev else "-")

p = g.get_path_handle('z')

q = []

g.for_each_step_in_path(p, lambda s: q.append(process_step(s)))

print(g.get_path_name(p), ",".join(q))

# z 1+,3+,5+,6+,7+,9+,10+,12+,13+,15+It’s possible to add and delete nodes from the graph using the python API:

We can also add edges:

And add path steps:

Path z now ends at 16+, and running the path enumeration code above would yield:

We can divide a node without breaking the paths that overlap it:

Assuming you’ve executed all the code up to this point, the paths now walk through new nodes 17, 18, and 19 in place of node 9.

g.to_gfa()

# ...

# P x 1+,3+,5+,6+,8+,17+,18+,19+,11+,12+,14+,15+ *,*,*,*,*,*,*,*,*,*,*

# P y 1+,2+,4+,6+,7+,17+,18+,19+,11+,12+,14+,15+ *,*,*,*,*,*,*,*,*,*,*

# P z 1+,3+,5+,6+,7+,17+,18+,19+,10+,12+,13+,15+,16+ *,*,*,*,*,*,*,*,*,*,*,*In this document, we’ve covered the basic concepts in the HandleGraph abstraction and used the odgi python library to explore some of them interactively. Although this interface is a work in progress, it should already provide enough material for researchers in genomics who want to work with genome graph data structures. HandleGraph implementations like odgi demonstrate that we can work with genome graphs even when they are large, with dense variation. These models lift limitations on graph structure that have been a persistent feature of other genome graph implementations. We believe that these limitations were motivated mostly by difficulty in managing the memory requirements of genome graphs. Given that this issue is difficult to resolve, we hope to provide a generic solution to it. This should provide a generic foundation for the use of genome graphs in bioinformatics, genomics, and population genetics.